2 years ago now, I wrote the above tweet, and I just wanted to post about this and the importance of high hurdle rates. My original goal in the 2020 Portfolio Letter was a nominal return of >13% p.a. (Since then I have compounded ~38% p.a.). I have thought about further increasing the bar in which I will consider investing in an idea. If you want to truly make life changing wealth from investing in stocks, you won’t get very far settling for average or even slightly above average returns. Of course there is no shortage of index fund advocates out there settling for ~8-10% market index returns, which are likely to get you rich slowly. However, I wouldn’t be here writing this if that was my goal, I would simply have bought an index fund and continuously added to that if I wanted that sort of return.

Investors that capitulate into using a market based discount rate are doomed for mediocrity and more importantly, look incredibly stupid when compared to an index fund investor who did the same with a fraction of the time spent to do so. At some point, there is a value you have to put on the time demands of running an active portfolio, and that value for me is extremely high. “This better be worth it” I tell myself constantly, and continuously raise the bar for what I deem to be worthwhile.

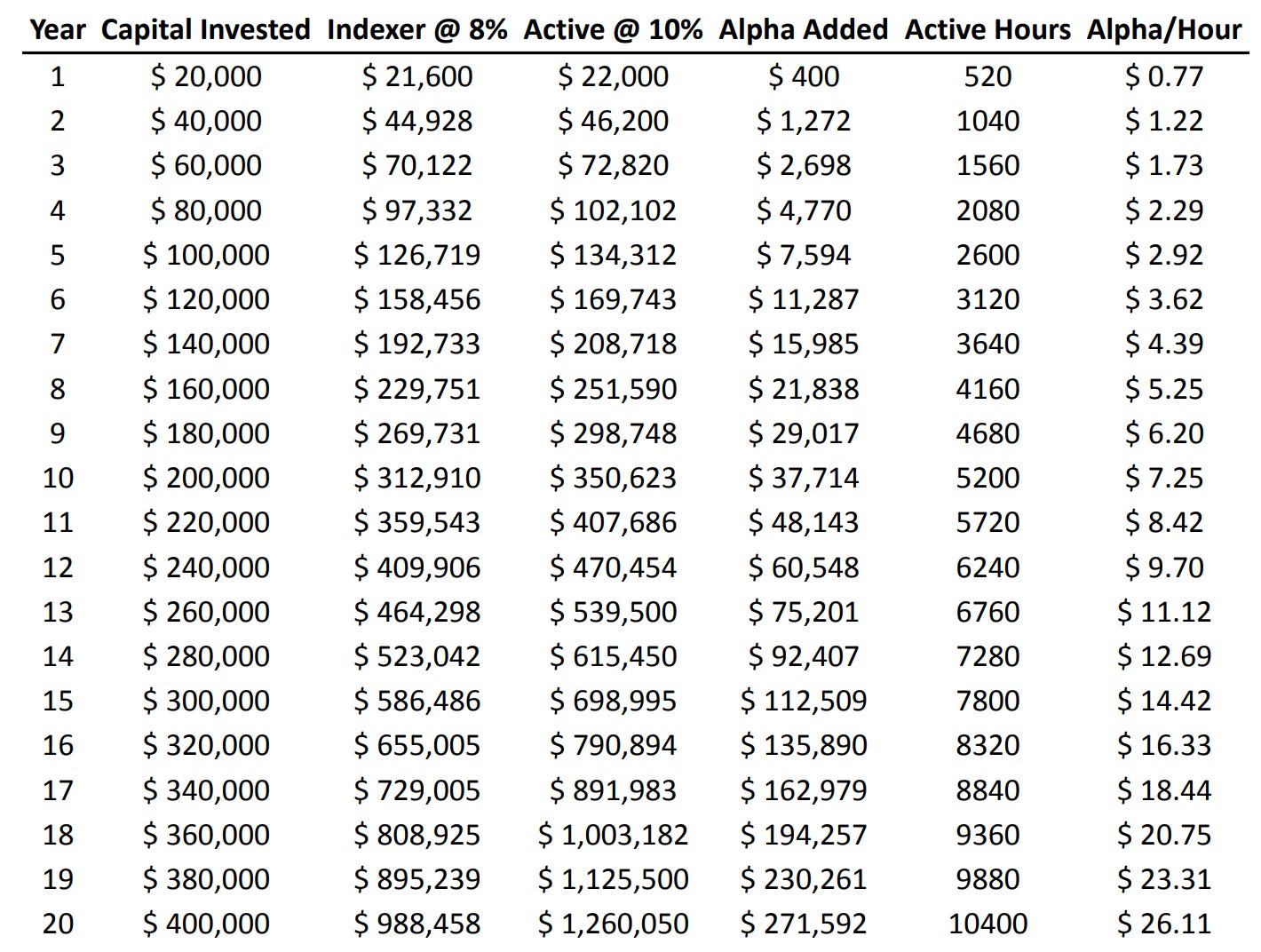

If you told yourself you were aiming for a 10% return over the next decade after tax and the market ends up doing 8%. You got 2% alpha that’s great! But the next step is how much time did you put into achieving that and how much capital did you put in over that time. Take the below example, where two investors put in 20k a year, one indexed and the other active. Additionally lets say the active investor puts 10 hours of research into investing per week. Ascribing an hourly value to the alpha generated looks like the below:

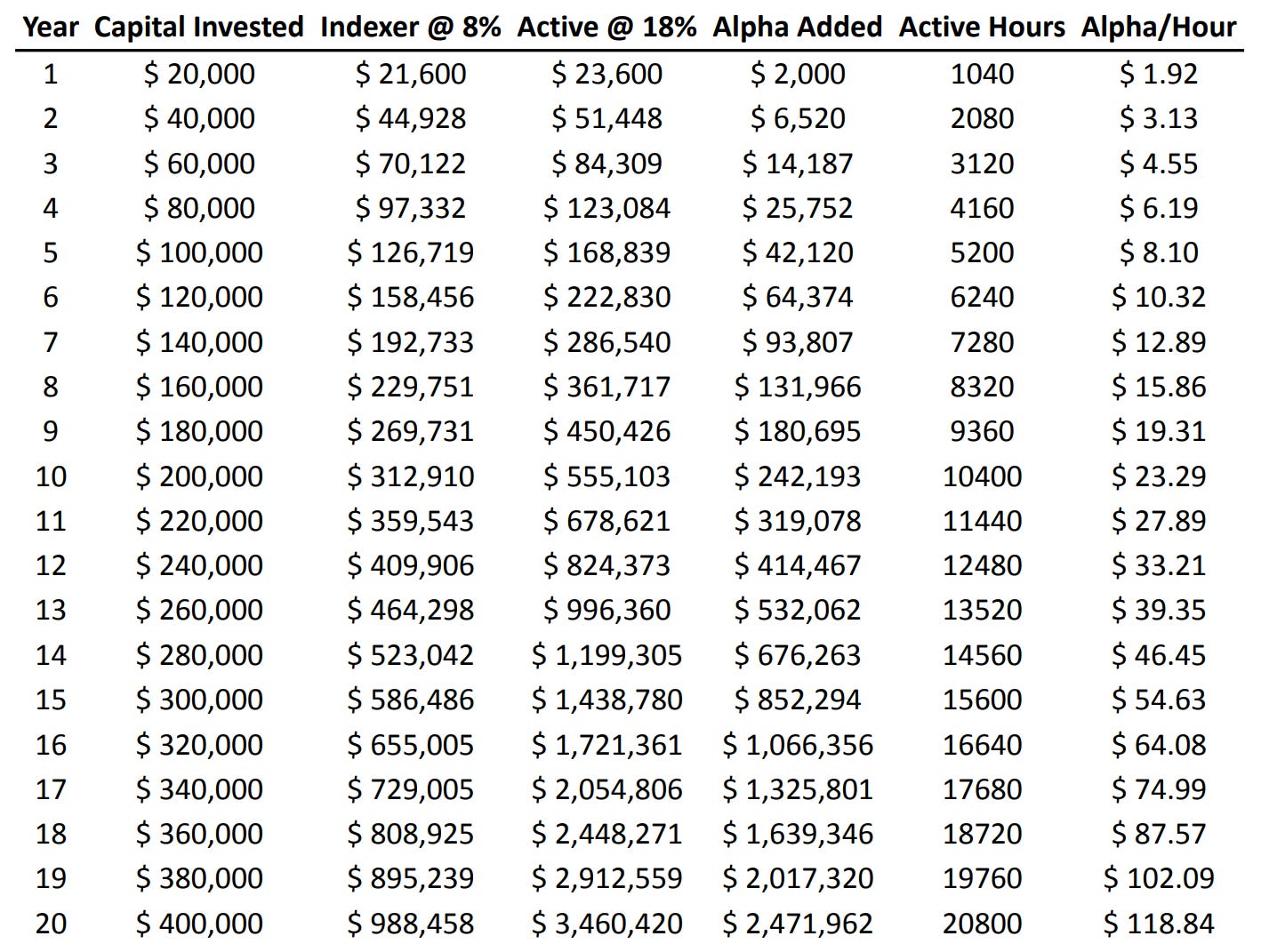

Now let's take the same example and suppose the active investor has a bar of 30% on new investments and falls short and only generates a 18% CAGR on his portfolio over the same 20 year time frame, and for good measure, let's assume that they also take 2x the amount of time than the other active investor.

You can see the point I'm trying to make here is that you better be getting your money’s worth for all this wasted time investing. For this reason the hurdle rate is a key determinant in my process and I wouldn't dare sacrifice on that as it would mean risking that my time is better spent doing other things. Taking the hourly rate, and comparing to the median hourly rate in Australia of $36 you can see that even in both cases, it takes a lot of time to eventually make the cumulative results of investing worth it. Of course if you start active investing with a larger capital base, it may be worth it from day 1, however at that stage, your time would also be worth a lot more, presumably having accumulated a skill-set to match a higher wage.

In any case, last year I said 13% was enough to reach my goals and that 3% was the premium I demanded as an active investor. I realise now that it was a huge mistake, and as such have increased my hurdle ~2-fold to >25% on new capital to ensure that capital isn’t a waste of both money and more importantly time.

“We postulate (and later even prove arithmetically) that the single-most important time determinant of stock market return is GROWTH in all its dimensions – sales, margin and valuation.”

~ Motilal Oswal, The power of growth in Wealth Creation

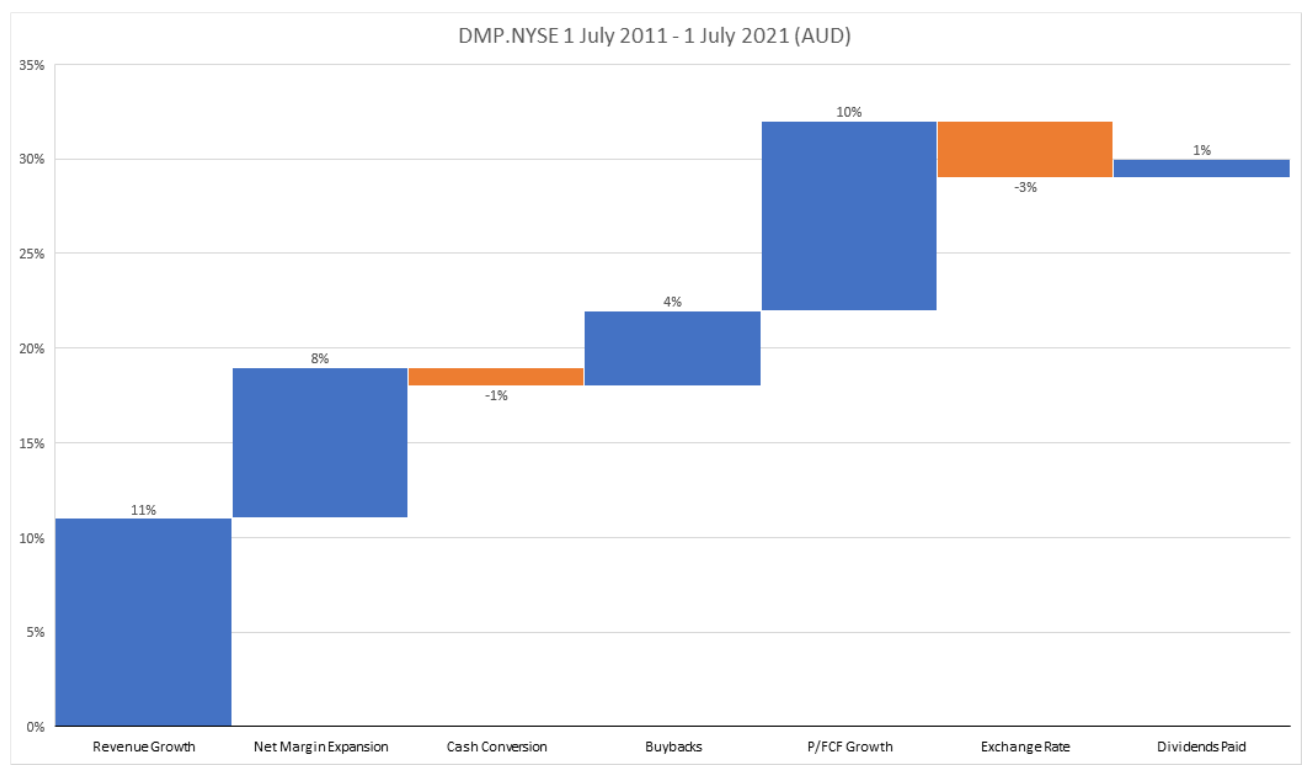

The next point I want to make is that you can extract returns from a large number of potential sources, and you should draw from various types of investors to incorporate all of this into your perspective when analysing a new business.

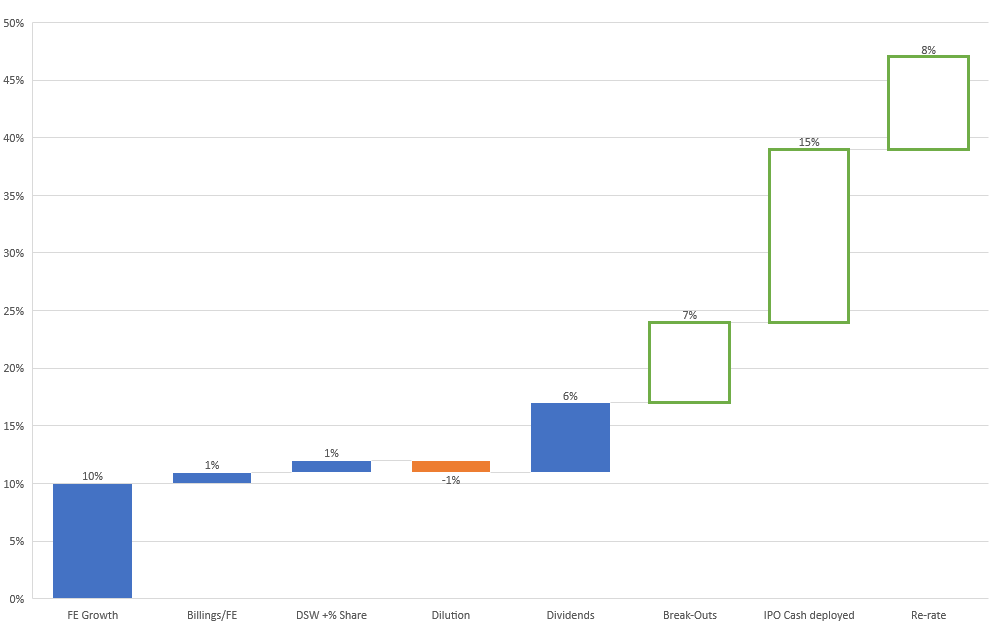

Above for US Listed Dominos Pizza (DMP.NYSE) I have broken down the total return in AUD which is ~30% CAGR in the 10y period (to 30 June 2021) into sources of return which you can see above. “Lollapalooza” refers to an end resulting from a large combination of factors, and stock market returns are no exception, above is only a small number of potential sources of stock market returns. Nevertheless, this is the approach in which you should view an investment, a three-dimensional one where you are looking not just at the dividend yield or the revenue growth in isolation, but at various potential reasons you will get a good return over time.

This is an increasingly important consideration in my own investments, and expanding my thinking vertically has assisted in broadening what I consider to be investable. For example, a business like Kelly+Partners acquires businesses at 1x sales whilst they double the margins, take out ⅓ of the working capital and get an initial uplift from the public/private valuation discrepancy. Further levers include the use of the spread in the cost of capital such as issuing debt at a 5% interest rate to acquire earnings under a 20x PE or diluting shareholders by 10% to increase free cash flow by 10%+. Such levers are integral parts of investing and oftentimes are difficult to predict. Nonetheless, I think it is without a doubt necessary to underwrite even a low possibility of it occurring and even better is when you pay a price that is so low, you don’t even need it to happen to get a great return.

Expanding on this, value investors want a business that is trading at an x% margin of safety. This is a concept that basically refers to the degree to which a stock is trading below the price you NEED to get a predetermined ‘discount rate’ or ‘expected return’ from the underlying cash flows of the business over time, including the cumulative value of dividends and the eventual price you sell it for, which is often predicted to be the ‘Terminal Value’ of the remaining cash flows in the business. Because these are uncertain predictions, an investor would apply a gap to allow for errors in their judgement. This section will talk about that gap and the variability around the “Intrinsic value”

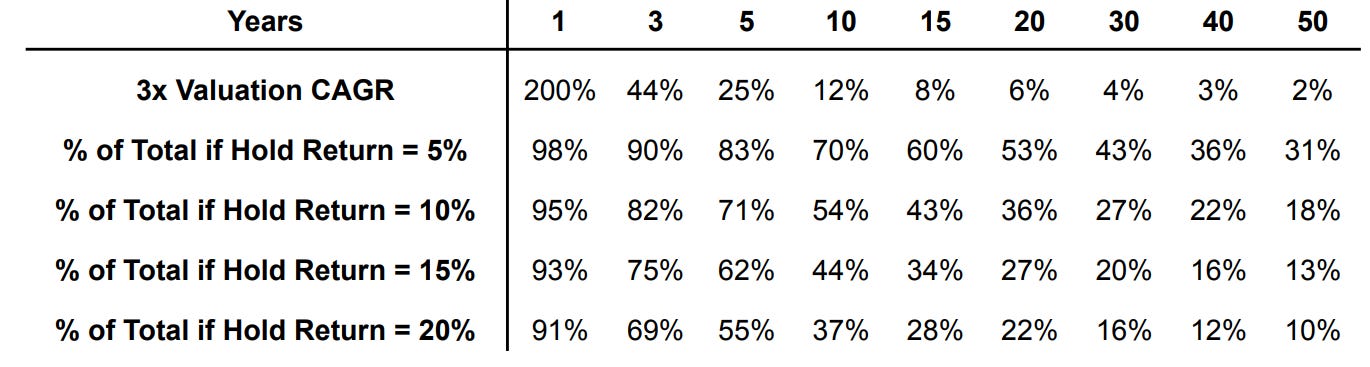

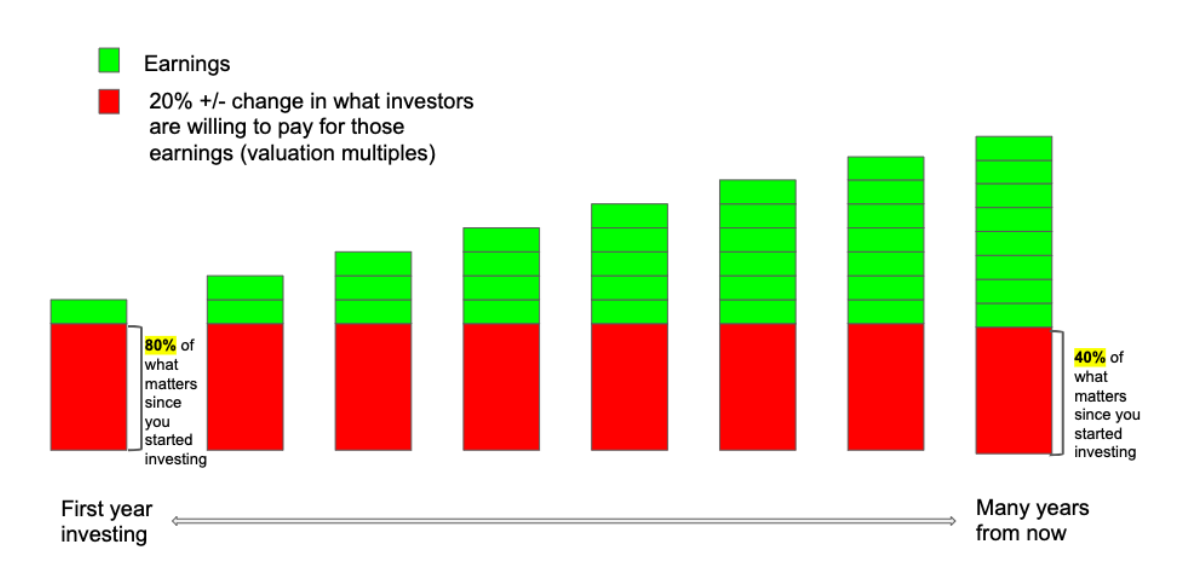

Assuming for example that the market should be paying 3x the current price for a business, that over different periods will add a boost to compound annual returns. What I also want to highlight is that this will matter more if the business is a slower grower as well, in fact, if the business compounds at 5% it can still make up a very large chunk of your returns over time. This would be realistic in the case of a traditional value investor buying slow growers or even stalwarts at cheap prices.

These figures are important as they will dictate what game you are looking to play. If you intend to hold a business for only a few years, the immediate valuation will likely matter most to you, however, if you are intending to find a business you can hold indefinitely, there is some nuance to what you need to outperform. First, if you don’t want to rely on valuation, you need an appropriately high growth rate and not overpay by an absurd amount. Second, if you want stable low return businesses, you need an absurdly low price to make up for the lack of compounded earnings. Third, if you buy a high yield business, you need to reinvest those dividends elsewhere with an appropriately high return.

The below chart is a great illustration of what I’m talking about. KPG valuation has driven ~75% of the total return for me where I expected it to account for ~35% of the return over 10 years.

The example above can be further analysed by implying that if a 20% upwards variation in the multiple is 80% of what matters, then the implied hold return is going to be 5% (20%/80% = 25% total). There are very extreme examples where the valuation multiplied by much more such as MTY Foods, an example covered in the book “100-Baggers” that experienced a move from 3.5 to 26x PE. A move that even over a 25 year holding period still approximates long term market returns from just multiple expansion alone. Therein lies the allure of finding extremely cheap, underappreciated businesses. Of course these don’t have to be high risk at all, you just need to know where to look, conduct deep and objective analysis and most importantly, swing with conviction when you see one such hidden gem...

My Portfolio Application

So i’ve broken down the hurdle i want, and the method upon which I intend to acheive it, which in short is strong lollapalooza events. Taking a publically researched positions from my current portfolio here is what I potentially expect.

Perhaps the best example from the portfolio due to the look-through nature of the business model. Here the returns expected come from a variety of areas, If you refer to my base case and then make some assumptions around incremental cash deployment and the massive IPO cash balance being deployed along with a modest re-rate, the lollapalooza becomes quite favourable, giving high return potential of close to 50% CAGR over a 5yr time span.

These waterfall charts help you break it down into attribution. But don’t get too excited, these are based on top of a base case scenario, deploying cash and getting a market re-rating are both very high uncertainty events that may not be realised. Furthermore, even the growth of the business has a reasonable level of uncertainty so this is really just the mid-point of probabilistic thinking to me.

Thank you for reading, if you have anything interesting to say or discuss please feel free to comment below or on twitter.